For the last few months, the Center for a Better South has been working behind the scenes with folks at the Southern Carolina Alliance and other organizations to push our South Carolina Work Group‘s goal of ensuring an application for a Promise Zone designation from the federal government on behalf of people living in the lower part of the state.

Today, we can announce that the application has been filed and, while we don’t know whether the Southern Carolina region will be named a Promise Zone, we’re tickled pink at the hard work of all involved.

To get an idea of what we worked on, let us encourage you to read this commentary posted earlier today by Better South President Andy Brack as part of his Statehouse Report weekly publication:

A promising opportunity for a poor part of the state

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher

NOV. 21, 2014 — Imagine if there were some kind of program — a little something extra — that could give pervasively poor places a better chance so they could be more like most of America.

Imagine how such a program could create better job opportunities to stabilize family finances, reduce crime to make communities safer and improve education so children could expand economic mobility.

In January 2013, President Obama announced a pragmatic effort to help overlooked places in America. In his State of the Union address, Obama said he would designate 20 “Promise Zones” — special urban, rural and tribal communities where the federal government would partner with communities to make life better.

What’s smart about this effort is how it doesn’t drop a big pot of money on poor communities. Instead they have to come up with real plans on how to fix things. Then they can apply for federal help through existing grant programs. But the bonus: communities that get the designation will get human capital — trained federal workers who will help make applications for existing grant money to grow jobs, reduce crime or improve education. For these regions with low tax bases, that’s practical help. Next, the Promise Zone communities get a few extra points when an application is scored — a little bump because they’re persistently poor areas with a lot of challenges. That’s smart, too, because it gives these areas a realistic chance to compete for funding, instead of always being on the short end of the stick because they’re small and often forgotten.

What’s smart about this effort is how it doesn’t drop a big pot of money on poor communities. Instead they have to come up with real plans on how to fix things. Then they can apply for federal help through existing grant programs. But the bonus: communities that get the designation will get human capital — trained federal workers who will help make applications for existing grant money to grow jobs, reduce crime or improve education. For these regions with low tax bases, that’s practical help. Next, the Promise Zone communities get a few extra points when an application is scored — a little bump because they’re persistently poor areas with a lot of challenges. That’s smart, too, because it gives these areas a realistic chance to compete for funding, instead of always being on the short end of the stick because they’re small and often forgotten.

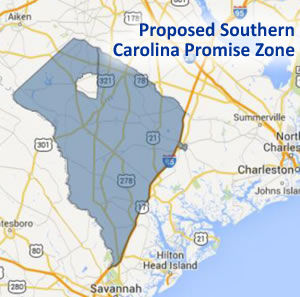

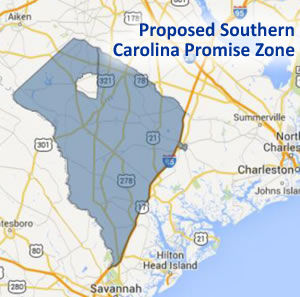

Today, South Carolina’s poorest region applied for a Promise Zone designation. The Southern Carolina Alliance (SCA), an economic development nonprofit that covers Allendale, Bamberg, Barnwell, Colleton, Hampton and Jasper counties, is leading an effort to secure the designation for just over 90,000 people in this southern tip of the Palmetto State.

In this area west of Interstate 95, the poverty rate is 28.2 percent, including one sector with a poverty rate just shy of 50 percent of residents. Unemployment is 14.8 percent — more than twice the state average. Crime rates are too high. The schooling that most kids get is substandard, recognized just last week by the state Supreme Court in a long-awaited landmark case on inequitable school funding.

As part of the Southern Carolina Promise Zone application, the SCA, in coordination with the counties, nonprofits and private entities, proposes to energize job growth strategies that would help small farmers grow foods to be sold in the state’s metropolitan areas and keep hundreds of millions of dollars spent on food in the Palmetto State. Some 90 percent of the $10 billion in food we buy in South Carolina goes out of state.

Other job growth strategies call for special attention to agribusiness, such as food processing plants; creation of construction jobs by rehabilitating poor housing and building more affordable housing units; growing green-related jobs through a program to upfit homes to allow residents to save on energy costs and implementing a proven program to boost financial stability of low-income families. Also proposed: a revolving loan fund to generate more small businesses; education measures for more job training to expand skill sets; scholarship programs; early reading help; more prosecutors to curb career criminals and gang activity; and a peer victim advocate program in local schools.

SCA leader Danny Black says his group wants the region to be named a Promise Zone because it’s just plain good for areas that have been ignored for far too long.

“It’s the correct area of the Southeast to do something like this because we are hurting in all of the areas that they want to touch,” he said. “It’s something that allows us to bring quality of life issues and economic opportunities to a part of the state that really needs it.”

Tim Ervolina, head of the United Way Association of South Carolina, said his organization is excited about the possibility of a Promise Zone in the Southern Carolina area.

“It’s not just about the additional resources,” he said. “It’s about the opportunity to use those resources to build lasting community infrastructure which can bring sustainable change.”

Indeed. It’s about time. We’re keeping our fingers crossed.