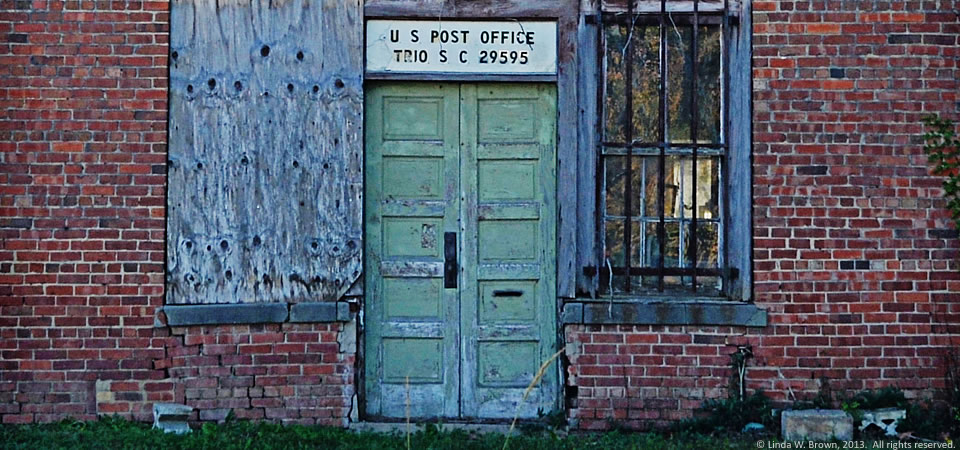

The front half of this old railroad depot in Ehrhardt, S.C., has been renovated into a place that reportedly has periodic auctions. The inside looks like a little cafe. The rear part of the depot, for which there are no railroad tracks these days, hasn’t been restored.

Ehrhardt, a town of about 600 people, is in rural Bamberg County where 27 percent of its 15,763 people live below the federal poverty level, according to 2012 Census estimates. The majority of residents are black (61.4 percent) with whites comprising 36.8 percent.

- QuickFacts about Bamberg County from the U.S. Census.

- Learn about Ehrhardt in Wikipedia.

Photo taken January 2014 by Andy Brack. All rights reserved.