Published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

By Andy Brack

There’s a vitality that runs throughout metropolitan Atlanta. Expensive cars are ubiquitous around Lenox Square. Neighborhoods in bedroom communities in Gwinnett and Cobb counties have good schools, libraries and a pretty good quality of life, despite some reminders of the Great Recession and, of course, traffic.

Vivacity, however, is harder to spot in a swath of agricultural Georgia that stretches across the middle of the Peach State, a rural sash of poverty where economic opportunity is tougher to find. The busiest place around might be a convenience store, as is the case in Leary in Calhoun County. Across the street is a full city block that has been abandoned. A couple of empty houses along Depot Street have been painted green or rusted red just to make them look less dilapidated.

Vivacity, however, is harder to spot in a swath of agricultural Georgia that stretches across the middle of the Peach State, a rural sash of poverty where economic opportunity is tougher to find. The busiest place around might be a convenience store, as is the case in Leary in Calhoun County. Across the street is a full city block that has been abandoned. A couple of empty houses along Depot Street have been painted green or rusted red just to make them look less dilapidated.

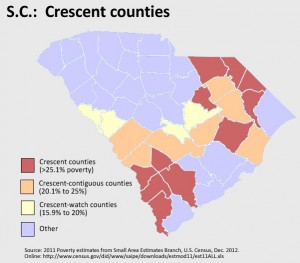

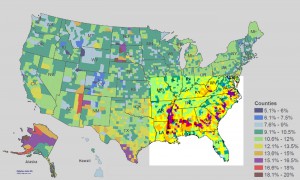

Across the South, from Tidewater Virginia through the eastern Carolinas along I-95, through the middle of rural Georgia and Alabama and to the Mississippi Delta, about 4 million people live in economically distressed counties. On a map, the area is crescent-shaped. It has higher rates of poverty, unemployment, single-parent households, chlamydia, obesity and diabetes. It’s easy to see that these areas correlate with another map — that of where enslaved people lived in 1860.

This “Southern Crescent” is a clear remnant of plantation life, a region that has been the soft underbelly of the Deep South for generations. Today, 150 years after the Civil War, it’s time for the Crescent to start receiving the same attention that Appalachia did in the 1960s War on Poverty.

It’s not all doom and gloom in Crescent counties. Lots of people have good lives. Some forward-looking communities have taken extra steps to plan and innovate. In recent years, Vidalia in South Georgia has branded itself as the go-to place for sweet, delicious onions. Prosperity shows throughout the town, but even today, 25 percent of the people in Toombs County live in poverty.

To focus attention on endemic poverty throughout the Crescent counties, the Center for a Better South offers a Web site — SouthernCrescent.org — to showcase life in the region. We hope to bring together nonprofits and foundations to fund research and studies on how to coordinate better and smarter delivery of services to infuse more dynamism in the region. The center encourages the White House to create a special national study commission to recommend federal and state policies to raise living standards and promote opportunity.

This effort may not cost a lot of money. If various state and federal government bureaucracies get out of their comfort zones and work with engaged rural communities, they can figure out ways to create more economic opportunities.

Ride the roads of Crescent counties in Georgia. It’s clear that rural Southerners want more opportunities for their counties. Now is the time to get moving so they don’t get left behind even more.

Andy Brack is president of the Center for a Better South (bettersouth.org) based in Charleston, S.C.